Project-based learning in the Chinese heritage language course/class in Finnish comprehensive education

Julkaistu: 22. maaliskuuta 2023 | Kirjoittanut: Paiwei Qin

Introduction

In this article, I attempt to share my reflection on my recent teaching practicum – Project-Based Learning (PBL) – in a group of Chinese heritage language learners in Central Finland. With the trend of global mobility and immigration, Heritage Language (HL) (oma äidinkieli) education is a growing phenomenon in Finland. According to the latest statistics, the teaching was given in 58 different language by Finnish local education providers (free of charge), and the total number of enrolled pupils was about 22,000 in 2021 (FNAE, 2022). In Finland, HL instruction usually starts from 7-year-old to 16-year-old, covering all grades in basic education, and its fundamental goal is to maintain and develop pupils’ mother tongues (Jyväskylän kaupunki, n.d.).

In recent years, many studies on HL education have drawn special attention to the pedagogical perspective. For instance, Bärlund and Kauppinen (2017) investigated the creation of authentic language learning materials via Active Library and an online cooperative learning forum. They analysed the created literature materials and transcripts of 10 pupil participants in German and Russian HL groups. The results show that although the assignments associated with children's literature in each HL raise pupils’ language awareness, the project is not as effective as researchers expected to facilitate pupils’ autonomy and acquisition of HL. (Bärlund & Kauppinen, 2017.)

Another study investigates the identity construction of Chinese HL learners through photography project-based learning (Li, 2019). She developed a project that requires the Chinese HL pupils to collect, produce, and report multimodal sources that could illustrate how Chinese and Finnish are present in their live. The findings suggest that the photography project is a pupil-friendly approach to encourage the HL learners to reflect on their bilingual experiences since the multimodal sources enable the pupils with different levels of HL proficiency to express themselves and see the diverse forms of connections between HL and Finnish. (Li, 2019.) Both studies have examined the innovative pedagogical approaches (i.e., introducing authentic literature and the photography project) to teach HL, which has paved the way for me to conceive my teaching practicum.

PBL module design and implementation

PBL is a student-centred and teacher-facilitated learning approach that can develop learning interests and practical skills through actively engaging in problem-solving and knowledge-building (Bell, 2010; Kokotsaki et al., 2016). In contrast to the traditional didactic approach, pupils are the principal actors in PBL, and their learning process consists of inquiries design, research plan and management, implementation, report, and reflection (Bell, 2010). According to learning outcomes in National Curriculum for heritage language teaching (7–9 grades)[1] (Jyväskylän kaupunki, n.d.), there are five educational tasks associated with diverse forms of HL: process and production, HL cultural competence, transferrable acquired linguistic skills into different subject learning, advanced language learning strategies, and study motivation. In response to these described learning outcomes, the pilot PBL study has the potential to facilitate the pupils to explore the topic – school life – closely related to their everyday lives, develop their HL competence in all types of language skills, and increase their understanding of target culture (in an aspect of education). Also, one prominent feature of PBL is teamwork, which can form a collaborative learning atmosphere (peer-scaffolding) and improve teamwork skills in HL class.

The idea of this PBL topic came from a question raised by one of the pupils in the target group, that is, “how does the daily schedule look like in Chinese schools?”. I could not answer this question in the first place because I have left primary and middle schools a long time ago, and the situation varies from region to region in China. Given my work nature as an in-service HL teacher and doctoral researcher in bi/multilingualism, I developed his question into this PBL pilot study (“校园一周One week in schools”). This PBL study aims to develop pupils’ multilingual competence, foster their understanding of educational culture in Finland and Chinese contexts, and cultivate their research skills (e.g., collecting and producing information and problem-solving).

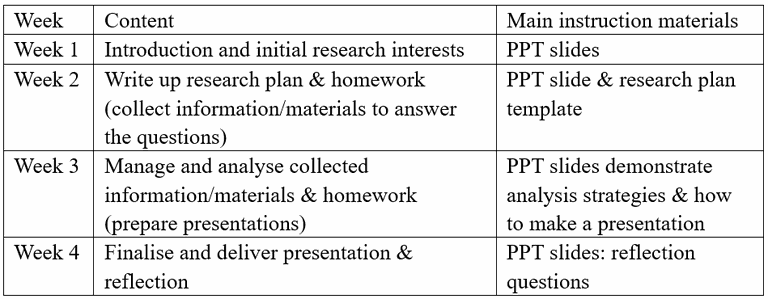

The target group of 6 pupils were 4, 5, 7 and 9 graders, who have studied Chinese for years. Most of them have intermediate-to-advanced levels of speaking and listening. At the same time, their literacy skills are varied, so one of their primary learning goals is to improve literacy competence. Given the feature of mixed levels/grades in this HL group, PBL can boost the merit of peer support by pairing the different-level achievers in mini-teams. Table 1 shows the PBL module schedule and content week-by-week[2].

Table 1. PBL module schedule (March – April 2022)

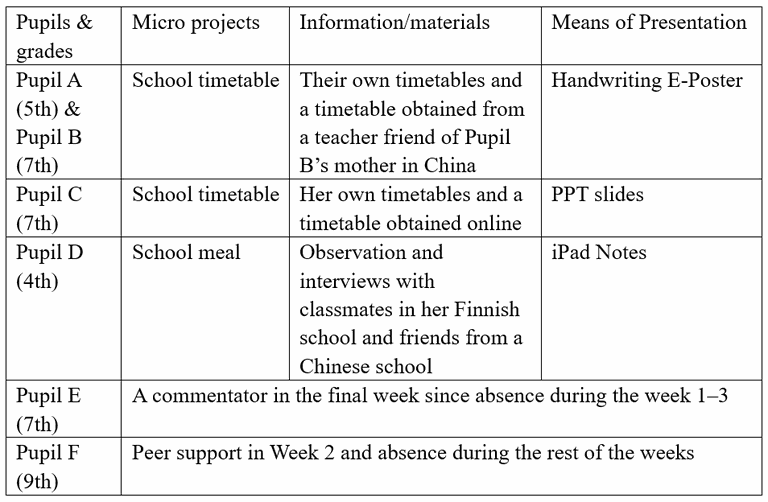

In Week 1, alongside the introduction of the PBL module, I oriented the pupils to the topic by posing general questions (e.g., “How is your school life in Finland?" and "What do you know about school life in China?”) to the group. These questions facilitate the pupils to brainstorm their initial research interests and pair themselves according to similar sub-topics. However, since two pupils were absent, only four pupils participated in Week 1 activity. Having discussed their initial interests, two boys (Pupil A and Pupil B) decided to work as a pair, while the other two girls (Pupil C and Pupil D) preferred working individually in the following three weeks. Table 2 illustrates pupils’ pair/individual micro projects.

Table 2. Pupils’ micro projects

In Week 2, I introduced the process and elements of the research plan by using a research plan template (e.g., title, research questions, methods to collect information/materials, expected results, and means of presentation/report). Then, the pupils designed and wrote up their plans accordingly, with the teacher’s guidance and language support. The homework for Week 2 was to collect the needed information/materials to answer their proposed questions. In Week 3, pupils were expected to bring the collected data and conduct analysis in groups, as the homework instruction required (e.g., to collect their own school timetables and timetable used in Chinese schools, or to ask Finnish classmates and friends in China about their school meals). However, not everyone brought the data they planned to have in the last week. Therefore, I comprised the scheduled learning tasks by differentiating my instructions to the progress of different micro projects. Nevertheless, all pupils in the lesson were able to get hands-on experience in analysing their available information/materials and promised to gather and analyse missing material before the final week.

In Week 4, pupils were expected to finalise their drafts and present their micro-projects; yet the pupils were at a different pace of their project research owing to the task delay of last week. Hence, I differentiated my instruction and scaffolded the pupils whose progress was behind. That lesson time was beyond schedule. Another unexpected problem occurred – the projector did not work when the pupils were ready to present. Hence, we had to postpone the presentation and reflection part to an extra week (Week 5). As illustrated in Table 2, the pupils presented their micro-projects one by one and other pupils were encouraged to ask questions or add comments. Finally, I guided them to do oral self-reflection on their performance in this PBL study activity.

Teacher’s reflection

Having reviewed the pilot implementation, I would like to self-reflect on some elements of teacher support in this PBL study. First, the main instructional language was Chinese, while other languages (e.g., English and Finnish) were used in the pupils’ learning process simultaneously since this PBL study encourages the pupils to explore school lives in cross-national contexts. Therefore, pupils made sense of their school lives by exercising their multilingual skills in processing and producing information. That mirrors the pedagogical function of translanguaging (García & Li, 2014), which encourages learners to creatively and critically deploy their entire linguistic repertoire for meaning-making in communication and collaboration. However, although I provided language support for some complex Chinese phrases/words (e.g., explaining and writing down corresponding Chinese-English words either orally or on whiteboard/paper with Pinyin phonetic marks), some pupils found it challenging to understand the research-related vocabulary and phrase their Chinese sentences in a formal genre. Therefore, it is recommended that teachers prepare a list of vocabulary used in research genres and school lives. In addition, it is also essential for teachers to instruct how to use the vocabulary list and supervise pupils to acquire those words. Otherwise, those vocabulary lists and written materials will be in vain, especially for demotivated pupils.

Second, since the learning activity of PBL includes presentation, it is suggested to teach pupils how to deliver and behave during presentations, such as a public speaking, ICT skills, and routines for listeners, because this set of skills is crucial for pupils to participate in the society of the 21st century (Ananiadou & Claro, 2009). In pupil self-reflections, presentation delivery is one of the frequently occurring topics. For example, one pupil said that she would adjust the fonts and format of her presenting materials to make the audience read them easily. Unlike adult learners, pupils are not necessarily familiar with ICT tools for presentation. Therefore, teachers should intentionally demonstrate what ICT customs are and how to use tools in their subjects.

Finally, it is often debatable how to group pupils. In this PBL study, due to the limited number of pupils, only one pair worked together, and others researched their topic individually. Although I have encouraged them to work in pairs that mix different-level achievers, the pupils did not seem interested in such pairing. Therefore, this PBL study failed to boost pupils’ agency in teamwork. Although it is crucial for teachers to respect pupils' choice for pairing/grouping, teachers could diversify classroom activities to increase inter-group/personal interaction and develop their teamwork skills, such as switching the (team) members between groups/micro-projects to share their own processes. Furthermore, one purpose of this pilot design is to create an opportunity for pupils to communicate with their Chinese peers by asking about and sharing each other’s school lives; thereby, they could use their Chinese language skills to explore and increase cross-cultural knowledge. However, most pupils reported that they did not have direct contact with pupils in China, so they chose to use second-hand data. Therefore, one possible solution is that teachers could prepare potential contacts of school pupils in China if any HL learner would like to carry out peer communication.

In short, this pilot study applied PBL pedagogy in a group of advanced Chinese HL pupils in a Finnish comprehensive school. In this project, pupils, as researchers, conducted their own micro-projects to explore school lives in Finnish schools and Chinese schools. Parts of the learning goals were achieved alongside pedagogical implications, while some possible improvements have been listed in this article.

[1] Due to most of the pupils are 7-9 graders in the target group, I reviewed and referred the National Curriculum for 7-9 grades.

[2] The weekly in-class learning was 1.5 hours in total. I divided into 2 sessions (45-50 mins/session) and used the first session for this pilot BPL module.

Paiwei Qin is a doctoral researcher at Centre for Applied Language Studies, University of Jyväskylä. She worked as Chinese heritage language teacher in Finland from 2019 to 2022.

Abstract in Chinese

随着全球化和人口流动潮,芬兰政府自1990年来逐步增强对移民融入与文化多元议题的关注。当前,芬兰各地政府依照其教育部的规定,为适龄学生(一般为七至十六岁)免费提供继承语(oma äidinkieli)课程,以保护和发展移民新一代的自身语言与文化。本文基于一位中文继承语教师的教学实践经历,探讨项目式学习(Project-Based Learning)在芬兰继承语课程中的试应用。在教师的指导下,六名混年龄组学生们(四至九年级)以芬兰和中国校园生活为话题,进行了为期四周的项目式探究学习,即提出问题、设计探究方案、收集信息和素材、分析整理、分享发现。该项目旨在提高学生多语能力,增进他们对芬中教育文化的了解,以及培养其探究学习技能。通过观察课堂和分析教学录像,本文从教师角度反思该教学实践中产生影响与挑战,并提出相关教学改进建议。

References

Ananiadou, K., & Claro, M. (2009). 21st century skills and competences for new millennium learners in OECD countries. In OECD Education Working Papers (Issue 41). http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/218525261154

Bärlund, P., & Kauppinen, M. (2017). Teaching heritage German and Russian through authentic material in Jyväskylä, Finland: A multiple case study design. L1 Educational Studies in Language and Literature, 17(Special issue), 1–23. https://doi.org/10.17239/L1ESLL-2017.17.03.05

Bell, S. (2010). Project-based learning for the 21st century: Skills for the future. The Clearing House: A Journal of Educational Strategies, Issues and Ideas, 83(2), 39–43. https://doi.org/10.1080/00098650903505415

FNAE (Finnish National Agency for Education). (2022). Omana äidinkielenä opetetut kielet ja opetukseen osallistuneiden määrät vuonna 2021. https://www.oph.fi/sites/default/files/documents/Omana%20%C3%A4idinkielen%C3%A4%20opetetut%20kielet%20ja%20opetukseen%20osallistuneiden%20m%C3%A4%C3%A4r%C3%A4t%20vuonna%202021_1.pdf

García, O., & Li, W. (2014). Translanguaging: Language, bilingualism and education. Palgrave Macmillan.

Jyväskylän kaupunki. (n.d.). Perusopetusta täydentävän oppilaan oman äidinkielen opetuksen tavoitteet, sisällöt ja oppilaan oppimisen arviointi. Retrieved October 26, 2022, from https://peda.net/opetussuunnitelma/ksops/jyvaskyla/liitteet/omaaidinkieli

Kokotsaki, D., Menzies, V., & Wiggins, A. (2016). Project-based learning: A review of the literature. Improving Schools, 19(3), 267–277. https://doi.org/10.1177/1365480216659733

Li, Q. (2019). A research on Finnish-Chinese children’s bilingual identity through multiliteracies: A case study of Chinese heritage learners in Central Finland. Master thesis, University of Jyväskylä. http://urn.fi/URN:NBN:fi:jyu-201906113124