Introduction

In November 2007, the Finnish Association of the Deaf organized a sign language seminar, with language policy and sign language teaching as the main themes. The seminar included a panel discussion with several experts in the field of sign language teaching on the question ‘Who is allowed to teach?’. This question was considered to be both very important and difficult for the audience and the Finnish Deaf community. The discussion was fruitful but no concrete answers emerged. The original reasons for raising this question can be explained in various ways:

The rapid, continuous increase in Finnish Sign Language (FinSL) research and since the early 1980s;

- An increase in the demand for sign language teaching in deaf schools, teaching of hearing parents of deaf children or people who just want to learn a new language, and training of sign language interpreters;

- A shortage of sign language teaching material;

- A short history of training in sign language teaching in Finland;

- The lack of up-to-date in-service training for graduates in FinSL studies or related fields that would allow them to develop their knowledge of sign language linguistics and pedagogy.

This combination of the recent history of FinSL research with the fast and increasing demand for sign language courses might have led to the appointment of unqualified sign language teachers, and even before the start of FinSL research. Nowadays, there is great variation among sign language teachers in Finland with regard to their linguistic, cultural and educational backgrounds. There is also great variation in the target groups of the teaching including deaf children in deaf schools, hearing students in interpreter education or parents learning to communicate with their deaf child. It is time we stopped and asked ourselves what we are actually doing.

Since the seminar in November 2007, we have been thinking a lot about ‘Who is allowed to teach?’, in order to get a clearer picture of what skills a sign language teacher needs. Instead of posing this vague question, we suggest that we should look at what sign language teachers should know or which proficiencies they should have in order to provide high quality sign language teaching.

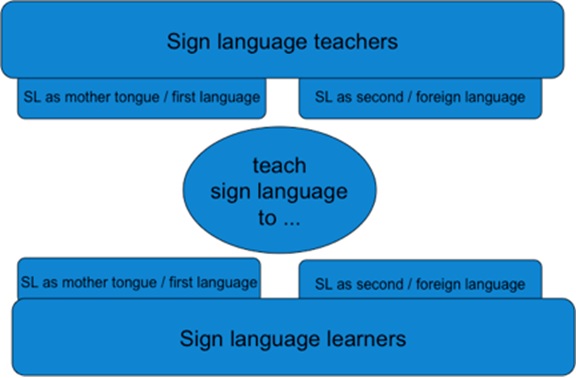

Our aim in this article is to share our opinions and stimulate some open discussion with the intention to raise the quality of formal or institutional teaching of sign languages in Finland. In this article we focus only on sign language teaching in educational settings. There are two sign languages in Finland, namely Finnish Sign Language (FinSL) and Finland-Swedish Sign Language (FinSSL), thus what we say here will apply to both languages, although there are differences between them (for example, there are far fewer FinSSL signers than FinSL signers, to the extent that FinSSL is classified as “severely endangered” by UNESCO, and much less research has been done into FinSSL). We will look into the different areas in which we think a sign language teacher should be proficient. As in every language teaching setting, there are two groups of people involved in sign language education: the teachers and the learners. The teachers may have FinSL or FinSSL as their mother tongue, second or foreign language, while the learners may be learning FinSL or FinSSL as their mother tongue, second language or foreign language, depending on their linguistic background and their age. This is schematized below.

Four Major Areas

As in any case concerning the teaching of a language, we consider that a sign language teacher needs sign language proficiency, linguistic knowledge, pedagogical knowledge and frequent contact with the sign language community. Above all, a positive attitude is required, an awareness that all these areas should be taken into consideration when teaching a sign language, and openness. We are fully aware that these are very broad areas, but let’s take them as the starting point for our discussion.

Each area can be viewed as constituting a sliding scale from virtually nothing to just about everything. Despite the fact that each area could be discussed in depth, here we will only provide a short description of each area, linking it to our personal teaching experiences, perhaps with example(s), and also to discussions on similar experiences with other sign language teachers and learners in this field. We start with a short description of each area, the scale on which it can be viewed and, if necessary, one or more examples.

Area 1: Sign language proficiency

The first area concerns the teacher’s sign language proficiency. We know that there is no sign language teacher who cannot sign at all and there is no teacher who signs perfectly. This applies to any language teacher. Although we all realize that one needs to be very proficient in FinSL and FinSSL to teach the language properly, evaluating how well a person can sign is sometimes difficult.

The fact that most people have not received instruction in and about sign languages might lead to a lack of cognitive tools for self-reflection or assessment of one’s own or others’ sign language skills. Having meta-linguistic skills in FinSL or FinSSL leads to an awareness of how to teach the language. The demands here can be very broad as several important features of a sign language are involved: knowledge of the signs and their variations, correct phonetic articulation, the use of articulation space, the difference in modality, the correct production of sentences and text, a knowledge of how to interact in different discourse settings, the ability to adjust the signing according to the target group, style or genre – and so much more. As it is complicated, this raises the question of how we evaluate our sign language skills if there are no or few tools to do so. This is something that has to be openly discussed and developed through self-reflection and discussion with other colleagues or students.

Example:

Evaluating someone’s signing proficiency is not always straightforward, even our own. An example from the learner’s point of view was shared with us by someone who studied FinSL for a year. She said that during her first year she thought the teacher was very skilled in FinSL and that she had learned a lot of new signs. Then she encountered the sign language community for the first time, and realized that the signs and sentence structures she had learned were different from those of the sign language community. However, much later she learned through discussions with the members of the community that the sentence structures she had learnt were not at all grammatically correct. This example shows that a student cannot evaluate a teacher’s skills – and perhaps the teacher can’t, either. The reason for this teacher’s unawareness can be ascribed to having neither meta-linguistic skills nor the ability to evaluate their own signing skills. Studies on sign language linguistics have given us some understanding of the structure of sign languages and the need for tools to evaluate sign languages.

Sign language teachers need both the skills and the tools to evaluate their own sign language skills. For this, the second area, linguistic knowledge is needed. All of the authors started to become aware of our own signing through studies in linguistics, and especially sign linguistics.

Area 2: Linguistic knowledge

No matter how fluently a teacher can sign, understanding the structure of FinSL or FinSSL as linguistic knowledge is a very important tool for teaching the language. The ability to teach and explain signs, sentences or text structures requires the ability to explain how the linguistic units of sign language are built in order to express meanings. Assuming that every sign language teacher knows something about the linguistic structure of the sign language in question, we can also assume that no teacher knows everything. However, knowledge about sign language linguistics and keeping abreast of the latest trends in sign language research are essential, given the recent expansion in this field.

Example:

Sometimes a learner might produce a certain sign with a different handshape than it should be. The teacher can correct this either by showing the correct sign more than once or by literally taking the learner’s hand and shaping it into the right handshape. Linguistic knowledge gives us the concept ‘handshape’; the teacher can tell the learner that the handshape is not correct, and the learner him/herself can then analyze his/her own handshape in this sign and look carefully at the teacher’s handshape in order to produce it correctly. This does not only apply to the parameters of a sign like a handshape, movement, hand orientation, place of articulation or non-manual element, but can also apply to sentence structure. It is better to explain the sign order in a sentence by using, for example, the concepts of ‘subject’, ‘verb’ or ‘object’ (etc.), than simply to say, ‘well, that is how deaf people sign’. This is comparable to an English teacher saying that you should say ‘an airplane instead of a airplane’ without explaining the rules for using ‘a’ or ‘an’ in English. It also often happens that teachers say there is no research on a certain topic when in fact there is. So, linguistic knowledge can be useful when teaching a sign language and so can following the latest research trends. It is the responsibility of every teacher to keep their linguistic knowledge up to date.

Area 3: Pedagogical knowledge

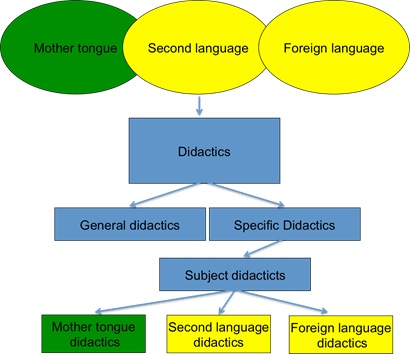

Proficiency in sign language and linguistic knowledge are, however, not enough. Knowing how to transfer your skills and knowledge to learners requires pedagogical knowledge. The scale for this area is similar to that of linguistic knowledge: no teacher will know nothing about how to teach and no one will know everything. How to teach a sign language depends above all on the learners’ linguistic background and/or aims. Teaching children requires a different approach than teaching adults. The teacher needs to know not only the general principles of didactics but specifically, how to teach languages. As FinSL or FinSSL can be taught as a mother tongue, second language or foreign language, both mother tongue, second language and foreign language teaching skills are needed. Different target groups learn sign languages very differently. Mother tongue teaching differs from foreign language teaching, but they are all called sign language teaching.

In addition, there are very few teaching materials for sign languages compared to what is available for spoken languages. Most sign language teachers have to create their own sign language teaching materials by producing pictures, videos and other materials. Producing materials that are appropriate for the setting and for teaching also requires skills and knowledge. In our opinion, more sign language teaching material needs to be produced, but teachers also need to get over their unwillingness to share their materials with others, whether this is caused by doubts about the quality of the material, some kind of economic constraint, or the fear of giving and getting nothing back. Changes are called for here.

Area 4: Frequent contact with the sign language community

Finally, we consider the fourth area, frequent contact with the sign language community. This is important for maintaining both one’s language skills and one’s knowledge of Deaf culture. Languages and cultures are constantly changing and this is just as true for sign languages and Deaf culture as for others. On language change, a person returning to the Finnish Deaf community after a 20 years’ absence will find that the signs for ‘window’, ‘orange’ or ‘water’ are no longer the same. The amount of finger-spelling may increase or mouthing might become less important from one generation to another. As for cultural change, the way deaf people think or behave in the community nowadays is not the same as it was in the past. Sociolinguistic variation should also be taken into consideration: the older generation can sign differently from the younger generation, and the people who live in the north of Finland can sign differently from those who live in the south. Language contact between FinSL and FinSSL or between Finnish and other national sign languages can also bring about changes in language structures. Without participating in changes in the Deaf community, it will be difficult for the sign language teacher to know how to teach.

Example:

Language contact comes about through transnational contacts between deaf people and the use of the internet, where people can upload videos in their national sign language(s). This language contact can result in borrowing signs from other sign languages. However, in recent years there has been increasing discussion within the sign language community in Finland about whether the signers should avoid certain borrowed signs like ACCEPT, APPROVE or AUSTRALIA or not for a number of reasons such as attitude towards borrowing signs or replacing existing FinSL signs by borrowed signs as they value FinSL signs as part of their heritage.

The desired profile of a sign language teacher

We have described the four areas of sign language proficiency, linguistic knowledge, pedagogical knowledge and frequent contact with the sign language community. We consider that awareness of these areas is important for teachers when teaching sign language as a mother tongue, second language or foreign language to different groups of sign language learners. Each area has its own sliding scale, from less to more. We propose that the level of what is required in each area always depends on the teacher’s background and the target group. We can ask ourselves what level is needed. This urgently needs to be discussed; we suggest that the required level on each scale mainly depends on

- the curriculum we are working with

- our target groups and their level

- whether we are teaching sign language as a mother tongue, second language or foreign language

- the students’ motivation to learn (e.g. an interest in learning something new versus a professional need)

This idea can perhaps support the community of sign language teachers to

- find our weakest skills and work on them

- find our strongest skills and develop and share them

- share our strengths and overcome our weaknesses through cooperation with our colleagues

We do not believe that proficiency in a sign language and linguistic or pedagogical knowledge are enough to make a good teacher; nor are having a perfect attitude and fluency in sign language. A good sign language teacher must have high standards in all four of the areas presented above.

As we said earlier, we would like to emphasize the importance of an open and positive attitude to teaching: a serious interest in each of the four areas outlined above; and commitment to our learners, to the language itself, and to the community whose language our learners are learning. If there is some kind of taboo lurking among these topics, it is time to bring it out into the open and discuss and work on it together.

Again, one might ask where on the scale is “good enough”? Time to continue discussing?

About the Authors

The authors all completed their Master’s degrees in Finnish Sign Language at the University of Jyväskylä. Danny De Weerdt is a doctoral student and university teacher at the Sign Language Centre in the University of Jyväskylä and Juhana Salonen works there as a project researcher. Arttu Liikamaa works for the Finnish Association of the Deaf, based in Helsinki, as a linguistic and pedagogic advisor for the Balkan countries. All of the authors have completed pedagogical studies and have advanced experience in the field of sign language teaching.

The authors would like to acknowledge Liisa Halkosaari and Gavin Lilley, both of whom have experience in sign language teaching, and Maartje De Meulder for their comments on earlier drafts of this article.

Suggested Readings

Jyväskylän yliopisto, Kielten laitos, Suomalainen viittomakieli, Tutkimus. https://www.jyu.fi/hum/laitokset/kielet/oppiaineet_kls/viittomakieli/tutkimus

Keski-Levijoki, J. (2008). (Toim.). Opettajankoulutus yhteisön luovana voimana – näkökulmia viittomakielisten koulutuksesta. Viittomakielisen luokanopettajakoulutuksen 10-vuotisjuhlakirja 17.10.2008. Julkaistu sarjassa Tutkiva opettaja – Journal of Teacher Researcher 6/2008. Jyväskylä: TUOPE. http://www.jyu.fi/edu/laitokset/okl/koulutusala/vkluoko/tietopankki/tutkimusta/viittomakielinen_juhlajulkaisu_nettiversio.pdf

Kulttuuria kaikille -palvelu. http://www.kulttuuriakaikille.info/viittomakieli.php

Laakso, M & Salmi, E. (2005). Maahan lämpimään. Suomen viittomakielisten historia. Helsinki: Kuurojen Liitto ry.

Soininen, M. (2016). Selvitys suomenruotsalaisen viittomakielen kokonaistilanteesta. Selvityksiä ja ohjeita 2/2016. Helsinki: Oikeusministeriö. http://www.oikeusministerio.fi/fi/index/julkaisut/julkaisuarkisto/1452773827455.html

Takkinen, R., Jantunen, T. & Ahonen, O. (2015). Finnish Sign Language. In J. Bakken Jepsen, G. De Clerck, S. Lutalo Kiingi & W. B. McGregor (Eds.), Sign Languages of the World: A Comparative Handbook. De Gruyter Handbook Series. Berlin: Mouton De Gruyter.

The Limping Chicken. DCAL: Why BSL linguistics matters for BSL teaching and learning (BSL). December 16, 2015. http://limpingchicken.com/2015/12/16/dcal-why-bsl-linguistics-matters-for-bsl-teaching-and-learning/