Supporting teacher collaboration in bilingual education: Sharing the CLIL pie

Julkaistu: 6. syyskuuta 2023 | Kirjoittanut: Josephine Moate

Bilingual education in the Finnish curriculum

Chapter 10 of the Finnish Core Curriculum for Basic Education (EDUFI, 2014) outlines the goals and conditions for bilingual education. Chapter 10 differentiates between smaller- and larger-scale bilingual education[1] and emphasises that students in bilingual education work towards the same goals as students studying through an official school language. Chapter 10 stipulates that bilingual education should not be detrimental to students’ learning and recognises that by integrating content and language learning, bilingual education can enrich and broaden students’ language repertoires without requiring them to surpass the A1 language learning targets stated in the curriculum.

Raising the profile of bilingual education within the core curriculum arguably transforms content and language integrated learning (CLIL) in Finland from a grassroots innovation to a policy-led approach. This change is partly indicated by the designated title ‘Bilingual Education’ rather than the non-Finnish term of CLIL. These different terms have led to some confusion in the field with teachers unsure whether they are providing bilingual or CLIL education. Although bilingual education and CLIL have somewhat different backgrounds which cannot be addressed here, in the light of the Finnish curriculum I would suggest that ‘bilingual-CLIL’ is perhaps the best term to describe the learning of different subjects through a non-official language, such as English, in Finland. Moreover, the administrative guidelines in the curriculum raise important questions, such as what expertise is needed to develop the dual-focused approach of bilingual education, how should teachers prepare for bilingual teaching, and how to support the bilingual development of students while also teaching through a foreign language.

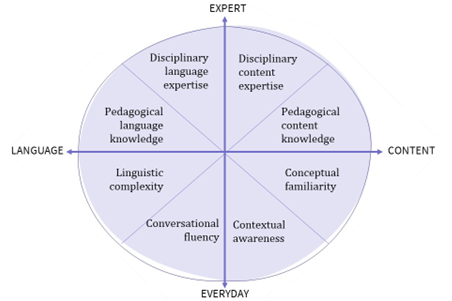

As a dual-focused educational approach bilingual-CLIL draws on the expertise of language and subject teachers. Teachers are often more used to enacting than verbalising their expertise, however, and this can make it harder for teachers to find a shared starting point when developing bilingual-CLIL education. The CLIL pie (Fig. 1) hopefully helps teachers to recognise and verbalise their expertise, to better understand the demands of bilingual-CLIL and to find practical ways of collaborating with colleagues.

Introducing the CLIL pie

The two axes of the CLIL pie highlight two important contrasts. The vertical axis acknowledges expert and everyday knowledge as important features of education. The horizontal axis acknowledges the dual focus of language and content, essential in all education, but particularly important when students learn through an additional language. These four quadrants highlight different forms of disciplinary, linguistic and pedagogical expertise needed in bilingual education. Each quadrant divides into two segments as explained below.

Figure 1: The CLIL pie

Quadrant 1: Expert-content

The expert-content quadrant comprises two segments. Subject teachers in Finland have a master’s degree in the subject they teach, e.g. mathematics, history, or biology. This expertise is represented by the disciplinary content expertise segment and includes different ways of seeing and understanding phenomena through the lens of a particular subject. Different disciplines explore and make sense of the world through a variety of modalities and activities, through subject-specific language and the particular conventions of the discipline. It is well-known, however, that disciplinary expertise does not mean that all experts can teach.

Understanding how to teach a particular subject, for example, how to build students’ understanding of time in history or the notion of place in geography, is expertise known as pedagogical content knowledge or PCK (Banks, et al. 2011). It is the PCK of teachers that enables them to anticipate which concepts might be difficult for students to grasp, such as force or energy: it is PCK that teachers use to develop favourite examples that illustrate difficult concepts and activities that foster understanding. It is the PCK of teachers that enables them to take discipline-specific activities, such as scientific experiments or multimodal representations, and to transform them into pedagogical resources or learning opportunities (Tytler, et al. 2020).

Quadrant 2: Everyday-content

The expert knowledge of the first quadrant is often introduced to students through everyday examples or experiences. Even those without a degree in biology can know or independently learn that plants benefit from quality soil, adequate light and water. Everyday conceptual familiarity connects with disciplinary expertise, but it is not the same as disciplinary expertise nor is it enough to know how to teach a subject: to be familiar with a concept does not guarantee the ability to be able to open up or examine a concept following the conventions of an expert community, but it is a useful starting point, a form of prior knowledge that teachers draw on to build connections and to foster new understanding (Scott, et al. 2011).

Recognising the value of everyday knowledge and being open to different ways of knowing is part of the contextual awareness of teachers, a pedagogical sensitivity to where students are coming from, the resources they bring and what it means to be a student and to be learning within a community. Contextual awareness is an important part of everyday life in educational communities, knowing that if students feel unwelcome or are doubted this can undermine their potential, knowing that students are more likely to risk learning and appreciate support when the activities that they are involved in are meaningful and help them to be at home in the world (Biesta, 2016).

Quadrant 3: Everyday-language

Another important form of expertise is conversational fluency. It is through everyday language that teachers build relationships with students and begin to share and develop understanding. As the educational pathways of students increasingly diversify, it is all the more important that teachers can use everyday interaction to expand and enrich the language repertoires and learning opportunities of students. Teachers can use everyday language, for example, to explain aims and activities to students. Conversational fluency is an important resource for teachers to be able to listen to students in order for them to learn how students see and experience the world, so that teachers are able to draw students’ attention to new possibilities and understanding (Biesta, 2022).

As the mantra ‘every teacher is a language teacher’ suggests, teachers are also expected to help students to develop more complex ways of using language (Moate, 2017). Whether students are moving on from preparatory Finnish classes, progressing through bilingual programmes or studying through their first language, students’ language development is not based on their own efforts alone. All students need ‘expert others’ to model different ways of using language and to provide a richer linguistic environment. While linguistic complexity is in part equivalent to disciplinary expertise, linguistic complexity is also similar to concept familiarity. A native speaker of a language might be able to use a range of language structures and to recognise when something is said or written inaccurately or unconventionally, but being able to explain what is ‘off’ and being able to intentionally teach language well is a different type of expertise.

Quadrant 4: Expert-language

Pedagogical language knowledge or PLK (Aalto, 2019) is the expertise that mediates and promotes students’ language development. PLK recognises language sometimes needs to be broken into smaller chunks and sometimes presented in longer stretches of discourse. PLK recognises that linguistic accuracy sometimes has to give way to creative exploration, that language frames can be useful for helping students to say, write or present more than their current level would allow, and that temporary support is a step towards independent expression. It is PLK that teachers use to translate between the language of a discipline and the everyday language students use to approach a subject.

Disciplinary language expertise includes the key terms and expressions of a discipline, the genres of history and science which disallow phrases such as ‘Once upon a time’ permissible in language arts, preferring different approaches to argumentation and inquiry. This is the expert language which can be alien to all students whether learning through an additional language or not. Disciplinary language expertise understands why it is more appropriate to say that plants absorb nutrients and that the earth rotates on its axis while orbiting the sun. Disciplinary language expertise presents the understanding of a subject, which is why even grammatically accurate statements – such as what a beautiful sunrise – can be considered inaccurate if they contravene disciplinary understanding.

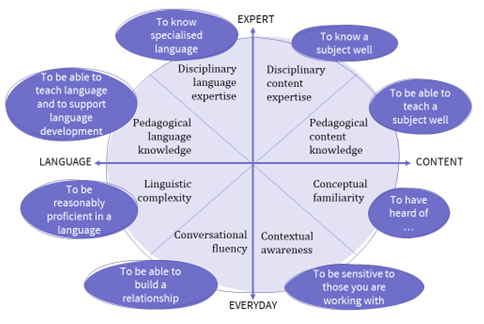

Figure 2: The CLIL pie with brief explanations

Figure 2 briefly summarises the different segments of the CLIL pie. Hopefully teachers can map individual and shared areas of expertise, as well as gaps and areas for development (Figure 3). Subject teachers may claim the disciplinary segments in the pie, highlighted blue in Figure 3. Language teachers might rightly claim more language-related expertise without claiming expertise in all disciplinary languages, highlighted green in Figure 3. As generalists class teachers will have some disciplinary content expertise, PCK and PLK, lilac in Figure 3, and as education specialists the particular expertise of class teachers informs their pedagogical sensitivity to students’ experiences and the importance of everyday interactions. Individual teachers will have different forms of expertise and the aim of the pie is to help teachers recognise the complementarity between different forms of knowledge encouraging partnerships to develop between teachers in bilingual education.

Figure 3: Mapping different areas of expertise

Teaching through an additional language

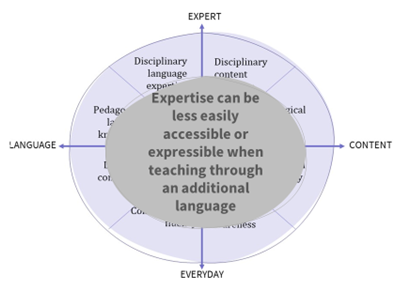

A recognised feature of bilingual-CLIL, however, is that students and teachers are often working through an additional language (Dalton-Puffer, et al. 2010). While CLIL has arguably been successful because experienced teachers have been prepared to reconsider and develop their practice, this is often a difficult experience and collegial support is important (Pappa, 2018). With the dual focus of CLIL, teachers are often working on the edge of their existing expertise. Moreover, when teaching through an additional language, expertise is often less easily accessible or expressible, automatic ways of working become an effort, sensitivity to students can be reduced and options can feel limited as responsibilities expand (Moate, 2011). As illustrated in Figure 4, teachers might feel that their expertise has shrunk or is no longer available.

Figure 4: Acknowledging the challenge of teaching through an additional language

In other words, teaching through an additional language often requires significant reorientation and renegotiation of established expertise. Subject teachers are still disciplinary experts, but it might be harder to explain or define key concepts and even if teachers can find the words, students might not understand as quickly. Familiar examples might be harder to explain, favourite jokes might not be funny and everyday examples that usually provide a ‘way in’ to new concepts, might be over-complicated by extra explanations. Teachers might also find it harder to gauge how students are making sense of new ideas. Everyday instructions or activities, such as posing questions to probe student understanding might not generate discussion in the same way or making notes on the board at the same time as listening to student contributions might not be as easy. Language teachers might not be aware of the significance of linguistic differences from a disciplinary perspective, and might be less aware of different modalities – and the importance of different modalities – in other disciplines, such as how art involves going beyond words, the entrainment of music, or translation as a mathematical concept.

These challenges call for conversations and collaborations that go to the heart of good teaching. Teacher communities possess a wealth of expertise. The current requirements for bilingual teachers in Finland emphasize general language proficiency but little attention has been given to the sophisticated expertise outlined in the CLIL pie. Bilingual teaching is not just a matter of swapping the language of instruction and study. The City of Helsinki has recently produced handbooks for CLIL in pre-primary and grades 1-6 which provide teachers with guidelines and principles for good bilingual education, as well as materials that are suited to the Finnish curriculum. As I have tried to highlight with the CLIL pie it is also important to recognise the different kinds of expertise that come together in bilingual-CLIL. What I hope to have highlighted is the need for subject, language and class teachers to collaborate, to find ways of sharing their respective expertise, to look across the broader curriculum that they are teaching to see how the integration of content and language learning can be a ‘win-win’ situation for teachers and students alike.

Conclusion

This article aims to support recognition of different kinds of expertise for bilingual education and the challenge of working through an additional language. CLIL teachers can, however, collaborate in a myriad of different ways (Moate, 2024) and the resulting pedagogical expertise is of benefit to students and teachers alike. Teacher collaboration is an under-used resource and within a changing educational landscape, it is all the more important that teacher colleagues are able to come together to offer the best education possible for as many students as possible.

[1] With 25% the key figure differentiating between language-enriched education, the designated term for smaller scale implementations of bilingual education.

Josephine Moate is a university lecturer in bilingual and multilingual pedagogy based in the department of teacher education at the University of Jyväskylä. This contribution is based on a talk prepared for the national bilingual education network event in Helsinki on 25th April 2023. This event brought together bilingual teachers from different parts of Finland and from different levels of education seeking a better understanding of bilingual education within the Finnish educational landscape.

References

Aalto, E. (2019). Pre-service subject teachers constructing pedagogical language knowledge in collaboration. JYU dissertations.

Banks, F., Leach, J., & Moon, B. (2005). New understandings of teachers’ pedagogic knowledge. In Teaching, learning and the curriculum in secondary schools (pp. 90-99). Routledge.

Biesta, G. (2016). Reconciling ourselves to reality: Arendt, education and the challenge of being at home in the world. Journal of Educational Administration and History, 48(2), 183-192.

Biesta, G. (2022). Have we been paying attention? Educational anaesthetics in a time of crises. Educational Philosophy and Theory, 54(3), 221-223.

Dalton-Puffer, C., Nikula, T., & Smit, U. (2010). Charting policies, premises and research on content and language integrated learning. Language use and language learning in CLIL classrooms, 7, 1-19.

Moate, J. M. (2011). The impact of foreign language mediated teaching on teachers’ sense of professional integrity in the CLIL classroom. European Journal of Teacher Education, 34(3), 333-346.

Moate, J. (2017). Language considerations for every teacher. Kieli, koulutus ja yhteiskunta, 8(2). Saatavilla: https://www.kieliverkosto.fi/fi/journals/kieli-koulutus-ja-yhteiskunta-huhtikuu-2017/language-considerations-for-every-teacher

Moate, J. (2024) Collaboration between CLIL teachers, In, D. L. Banegas, & S. Zappa-Hollman, (Eds.). The Routledge Handbook of Content and Language Integrated Learning. Taylor & Francis. p.171-191.

Pappa, S. (2018). "You've got the color, but you dont't have the shades": primary education CLIL teachers' identity negotiation within the Finnish context. Jyväskylä studies in education, psychology and social research, (619).

Scott, P., Mortimer, E., & Ametller, J. (2011). Pedagogical link‐making: a fundamental aspect of teaching and learning scientific conceptual knowledge. Studies in Science Education, 47(1), 3-36.

Tytler, R., Prain, V., Aranda, G., Ferguson, J., & Gorur, R. (2020). Drawing to reason and learn in science. Journal of Research in Science Teaching, 57(2), 209-231.